It has been a very long time since I last wrote here. Many things have happened, not the least a pandemic. I have often thought of returning to this blog, but things got in the way. Over the last couple of months, however, my fingers have been itching more. So here I am.

While I have not blogged for several years, I have certainly been very busily writing. One area in which I have become interested is early Christianity, and its attitudes towards healing, motherhood, and children (sometimes all at once). While working on an article on lactation cessation (which you can access in full here), I encountered the story of a little child who cried so much after being weaned off the breast that he risked losing his sight. His nurse brought him to the church of Saint Thecla in Seleucia, where he was healed (Life and Miracles of Saint Thecla 2.24). Who then was this Saint Thecla who could achieve the miracle of calming a toddler?

Thecla was a very early Christian, a follower of Paul of Tarsus. Her life is told in the early Acts of Paul and Thecla and expanded on in the later Life and Miracles of Saint Thecla (the link is to the edition of the text, with a French translation). She was a noble and wealthy young woman from Iconium (now Konya, in modern Turkey), betrothed to Thamyris. One day, Paul came to the city and stayed in the house next to hers. From her window, she listened to the noble Christian and decided to devote her life to Paul and to Christ. For perverting the young girl, Paul was thrown in prison. Thecla, under the cover of darkness, went to find him, having bribed the prison guard. When her subterfuge was discovered, Thecla was condemned to death by burning. She was saved by rains, which conveniently killed many in Iconium.

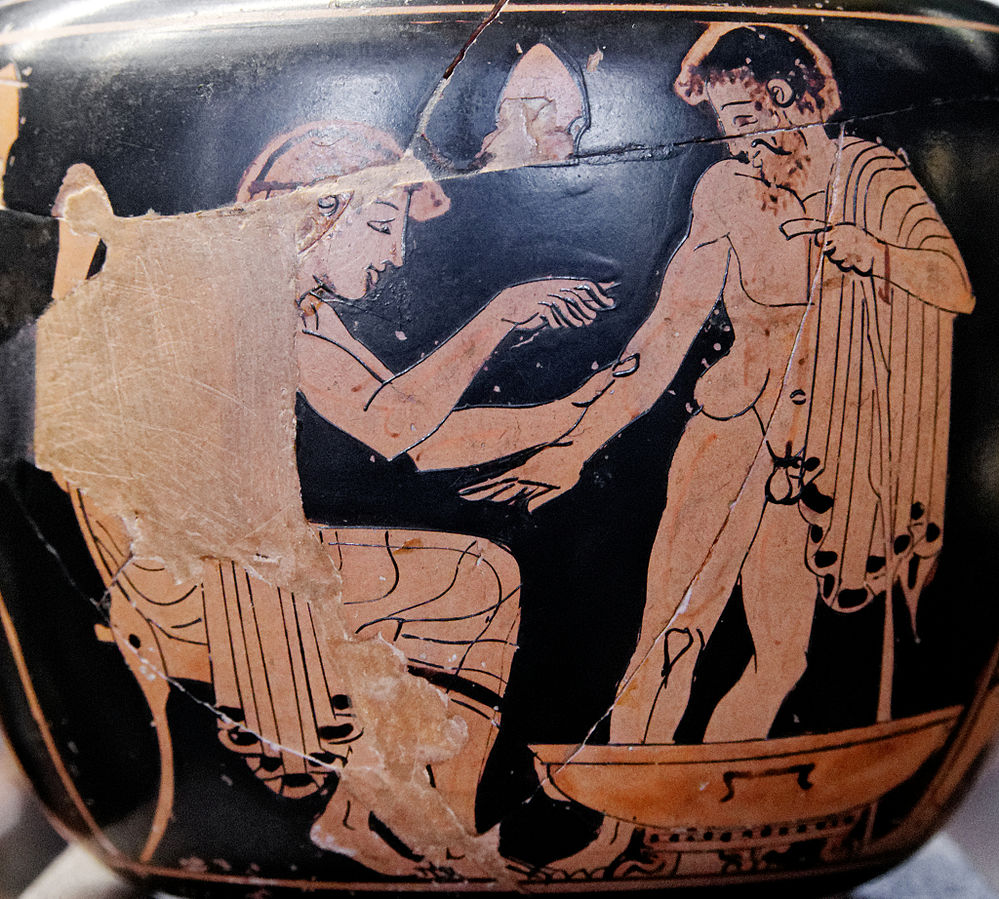

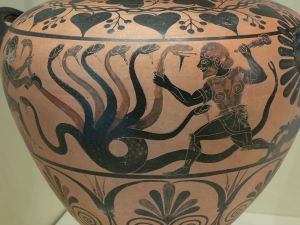

Thecla then followed Paul to Antioch (of Syria), where she stayed with a woman named Tryphaena who had lost her only daughter. There, a man named Alexander tried to seduce the holy woman, to no avail. He managed, however, to convince a local magistrate to condemn Thecla to death – again. This time, she was attacked by wild beasts. One of the lionesses sent to kill her laid at her feet; other beasts killed each other. The story is rather wild (in more senses than one), and Thecla also threw herself into a pool of bloodthirsty seals (I know, this makes no sense!), to seek death while auto-baptizing. Nothing worked. She survived.

Thecla eventually settled in Seleucia (now Silifke), where she disappeared – alive – under the earth. Thence she offered healing, as if it came from springs, both during her long life and once she had departed this earth. The site became one of pilgrimage for those who sought healing.

Saint Thecla may not be particularly known, but she has several shrines. One, it happens, not far from Wrexham, where I often go to visit family. For the first time today, I visited Llandegla (literally, Thecla’s village). It is a lovely little village with a church devoted to Saint Thecla (the current church is Victorian), and a healing well. The well was particularly reputed for healing epileptics, who had to visit the well, then sleep in the church, in the company of a cockerel. If that cockerel died during the night, the person would be freed from their epilepsy. To anyone familiar with the cult of Asclepius, much of this will sound very familiar – healing cults can be rather formulaic.

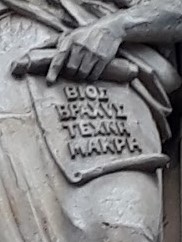

It is possible that Roman soldiers brought the cult of Saint Thecla to Wales. Some Roman artefacts were indeed found at Llandegla, including in the well itself. You will find information on some of the artefacts in the Portable Antiquities Scheme database. I’m particularly interested in this copper alloy cosmetic pestle.

Today, visitors are more likely to visit Llandegla while walking on Offa’s Dyke path, but if you are interested at all in healing sites, do pay the well and church a visit.